The Athenaeum Society

of

Hopkinsville, Kentucky

History Beneath Our Feet

Presented by Wynn L. Radford III, April 2018

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Of the Athenaeum members in this room, how many have a major or minor in archeology or

anthropology? How many members have experienced the wonder and awe of finding a projectile point in their backyard or along the banks of Little River?Thinking to yourself, what

are your top three-five immediate thoughts about NativeAmericans who previously lived in

Christian County? I imagine each member’s thoughts focused from 1500 AD forward, or after

the Europeans began to settle theAmericas. Quite frankly, until February 16, 2016 I had never

given serious thought concerning NativeAmerican history in Christian County. That changed

when Linda and I were waiting for aTPAC play in Nashville. We wandered into a national

archeological conference featuring Missippian effigies found along Kentucky and Middle

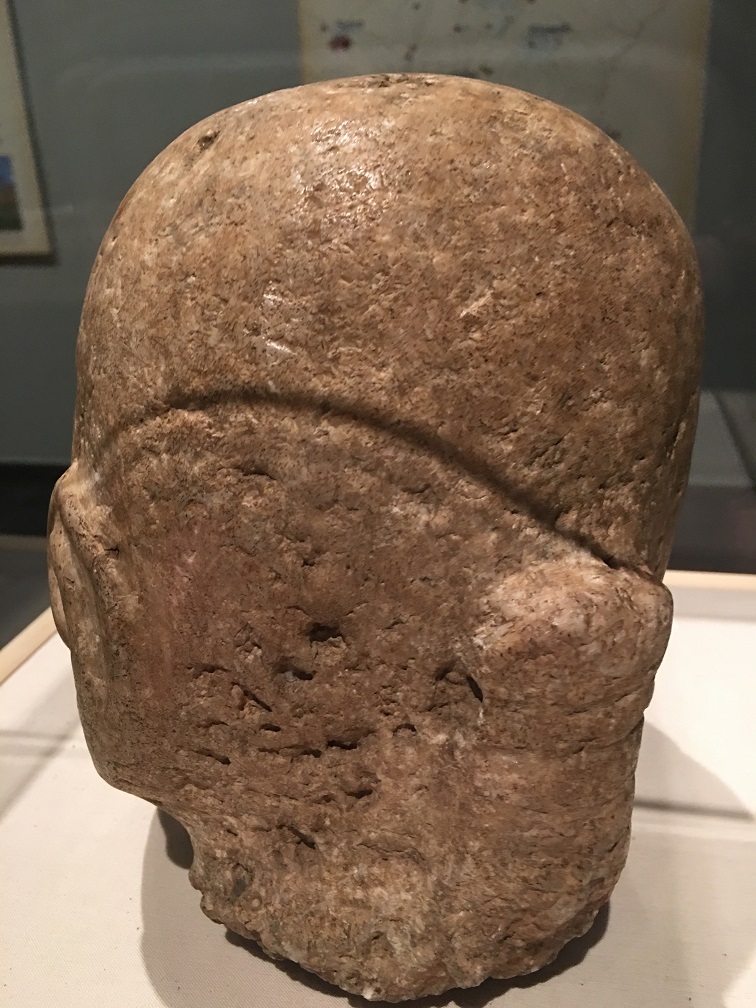

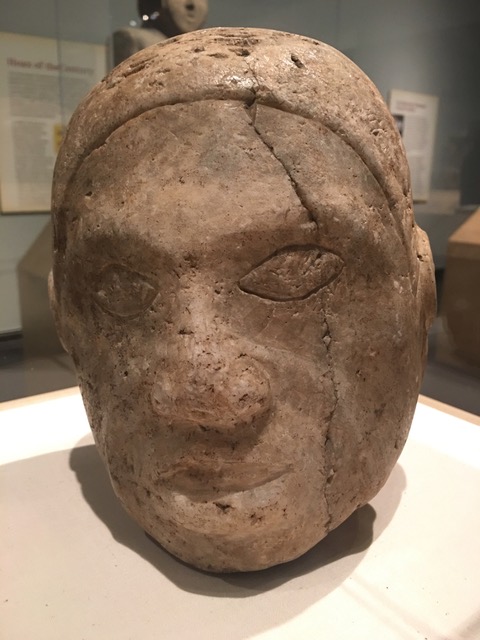

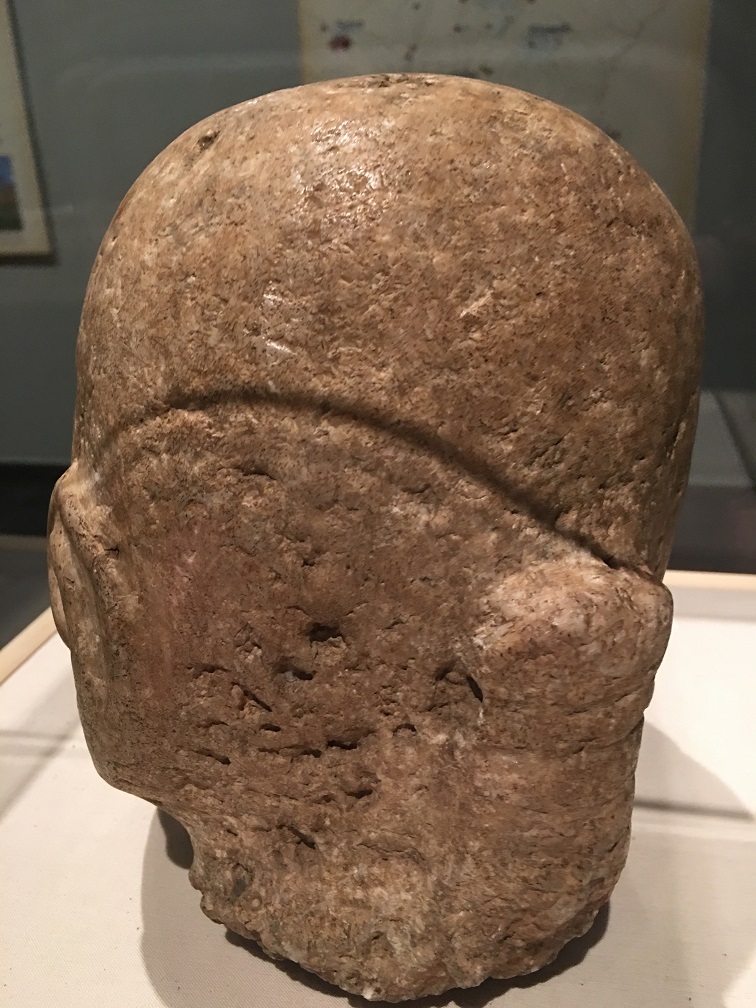

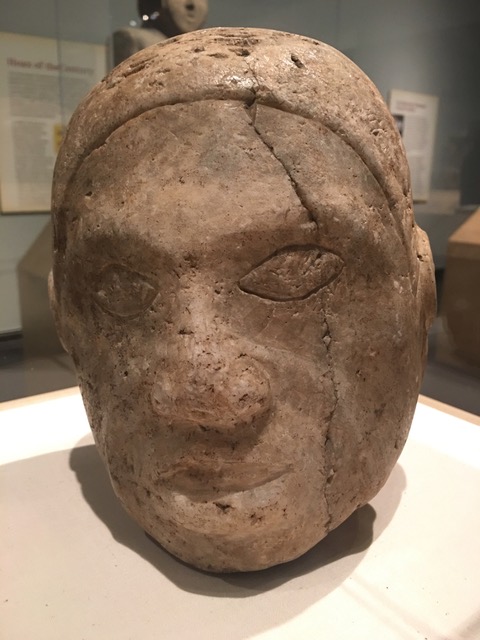

Tennessee rivers. I was immediately dumbfounded when I saw this particular

effigy on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NewYork City.

This effigy was identified as “found on the Wallace farm in Christian County, Kentucky in 1887”.

Imagine finding this distinctive effigy in your backyard?! If one looks closely, the effigy has the

facial characterisitcs of a Mayan and is made of a stone not common to Christian County,

possibly marble.

As one who lives within 100 yards of Little River and routinely finds broken

flint and projectile points while walking our dog my curiosity was immediately piqued. Since

that day in Nashville I have tried to better understand who, why, and what happened to the

people who made the Christian County effigy? Like Don Quixote and a somewhat reluctant

Sancho Panza, Linda and I have since visited Indian mounds in Kentucky, Missouri, Illinois,

Louisiana, Alabama,Tennessee, and Florida. I have since met many fascinating people and been

welcomed into the sometimes closed world of NativeAmerican artifact collectors. For purposes

of this paper, my goals are to better understand the Moundbuilders and the business of Native

American artifact collecting.

| |

The 'Mayan' figurine The 'Mayan' figurine

|

|

|

As seen in these photos, all Indian mound sites appear to have utilized effigies in some manner,

whether people or animals. Effigies were usuually made of flourite, flourspar, or

low grade marble. The largest effigies were usually 12-18 inches high and often found in a

male/female pair. Some archeologists suggest the effigies were used to enhance agricultural

fertility or to honor a particular leader. Effigies are often found on the edge of a settlement,

suggesting the effigies were hidden or dropped while the settlement was under attack. Possibly,

as in the Old Testament, settlements attacked neighboring settlemets to prove their god was

more powerful. What is remarkable about the Christian County effigy [not shown] is the size of the head and

the lack of a body. One has to wonder if the head was decapitated or perhaps part of a larger

effigy that was never completed? | |

NOTE: some photos in the original paper are omitted

|

|

|

|

| Mound with ramp for tourists | Multiple mounds at one site | Cahokia mound with St Louis in background |

Today, the Native American tribles that most people think of living in Christian County include

the Shawnee, Cherokee, Choctow, and Chickasaw. Of the six most recognized archeological

periods (Paleo (15,000-8,000 BC), Archaic (8,000-1,000 BC), Woodland (1,000 BC-1,000 AD),

Mississippian (800-1450 AD), Historic (1450 AD-1838 AD, and the Present (1838-today), we

will focus on the Moundbuilders, specifically the Missippians. The Mound-builders lived in

Christian County beginning 5,000 years ago and the Mississippians approximately 1,200 years

ago. Rather than tribes, imagine the early settlements along Little River as

neighborhoods of perhaps 50-200 people who lived around the bend or on the other side of the

river. Most local settlements were part of an extensive trade network with accces to the Little,

Red, Cumberland,Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers. (Imagine such rivers as early

interstate highways). Settlements would have actively traded for products such as flint, tobacco,

corn, sea shells, and copper.

One of my biggest surprises in researching this paper was to learn Christian County has long

been nationally recognized as a fertile area for excavating NativeAmerican artifacts. The

following is an exert from a 6/13/1902 advertisement in the Hopkinsville Kentuckian from

Warren K. Moorehead of Harvard University and the Peabody Museum inAndover,

Massachusetts (Photo 21). Having heard that Chrisitan County contains many “Indian relics”

that should be preserved, Moorehead appealed to local farmers:

“I am persuaded that there may be persons who have found some remains of the ancient

Indian tribes, “Mound builders,” etc. and that, possibly, they would be willing to send

them to us. We shall be glad to pay express charges on any and all boxes of specimens

sent to us, to mention the gifts in our report, and to give the donors due credit in our

exhibition cases.

All these axes, pipes, spear heads, clay vessels and “strange stones” should be carefully

preserved somewhere, where they may be of service to the public and to science.

Archeology-technically followed- is a new science in the United Sttes and it is more

important than the average reader imagines, for the “stone relics” have a direct bearing on

the antiquity of man.”

Additional research indicates that a 9 ¾ inch effigy found near Canton, Kentucky (near the new

Lake Barkley bridge) was presented to Thomas Jefferson on July 8, 1790. The Canton effigy

was the first of five pieces of Native American figural sculpture kept by Jefferson in his “Indian

Hall” at Monticello. Other local Indian mounds have been confirmed in Linton, on the Hadden

site in Elkton, the McRay mounds northeast of Hopkinsville, sites in Todd and Logan counties, a

now flooded mound at Jonathan Creek on Kentucky Lake, on the Fort Campbell military

reservation, and near Dover, Tennessee. Illustrating the active imagination shown by many

collectors, some speculate that the far side of Riverside Drive in Clarksville was once a large

Indian mound complex visited by De Soto.

Since 2016 I have walked thorugh many local fields and along riverbanks trying to “ . . . think

like a Native American.” My personal belief is that many Indian mounds existed along Little

River but have since been leveled due to farming, flood control, and commercial development.

As one local property owner who lives on Little River stated, “I may have the largest collelction

of Native American artifacts in Christian County, but they are all underground in my backyard.”

Further research indicates that the UK Department of Anthropology and Archeology conducted

two professional excavations, the Duncan site near Linton in 1929 and the Williams site near

Trenton, Kentucky in 1931 (Photo 22).

The Mississippian’s 650 years represent but a brief time period from an archeological

perspective, ranging from Wisconsin to Florida and from the Carolinas to Texas (Photo 23-24).

Archeologists estimate that as many as 100,000 Indian mounds once existed across the United

States and are now estimated at 10,000. A goal when I began this paper was to purchase

projectile points from each of the major time periods and exhibit at tonight’s meeting. However, I

soon realized that depending upon the grade of the objects such a project would cost between

$1,000-$25,000. Saving the business of purchasing and selling Native American artifacts for

later in this paper, let us now examine the earliest period in which Native Americans are known

to have lived in Christian County, the Clovis period.

In somewhat of an aside, the Clovis period is important becaue one of the nation’s amateur

Clovis experts lives in Christian County, CarlYahnig. Carl was gracious enough to meet with

me and discuss his vast knowledge about the people who walked across our backyards from

20,000–8000 BC. Due to a lifetime of hard work, Carl has amassed one of the largest personal

collections of Clovis points and fractures in the United States and is on a first name basis with

professional archeologists at Harvard. Carl described how such people most likely walked from

Siberia across the Bering Straight throughAlaska and over thousands of years traveled eastward

to the Mississippi River. Some archeologists believe, as similar Clovis points have been found

in southern France and northern Spain, that Paleo Indians travelled westward from France,

Greenland, New York and Ohio. A Clovis point is longer and narrower than the projectile points

with which we are most familiar. Early hunters would have used a spear with a Clovis point to

thrust into the side of a mastadon, giant sloth, or Sabre tooth cat. Imagine one of these animals

eating leaves from a tree in your backyard 10,000 years ago.

Now, let us fast forward to when local Native American settelments evolved from a

hunter/gatherer to an agrarian society. Due to the importance of water needed to travel, drink,

and wash, most Native American settlements lived within 500 yards of a navigable waterway.

Until viewing the Christian County effigy I never fully apprecaited the complexity of Native

American commerce. Today, most people identify corn and tobacco as Christian County’s

primary products. I believe the Mississippians would have valued the St. Genevieve chert found

along Little River as our county’s most highly valued trading product. Christian County chert

has been found in settlements from Ohio to Louisiana.

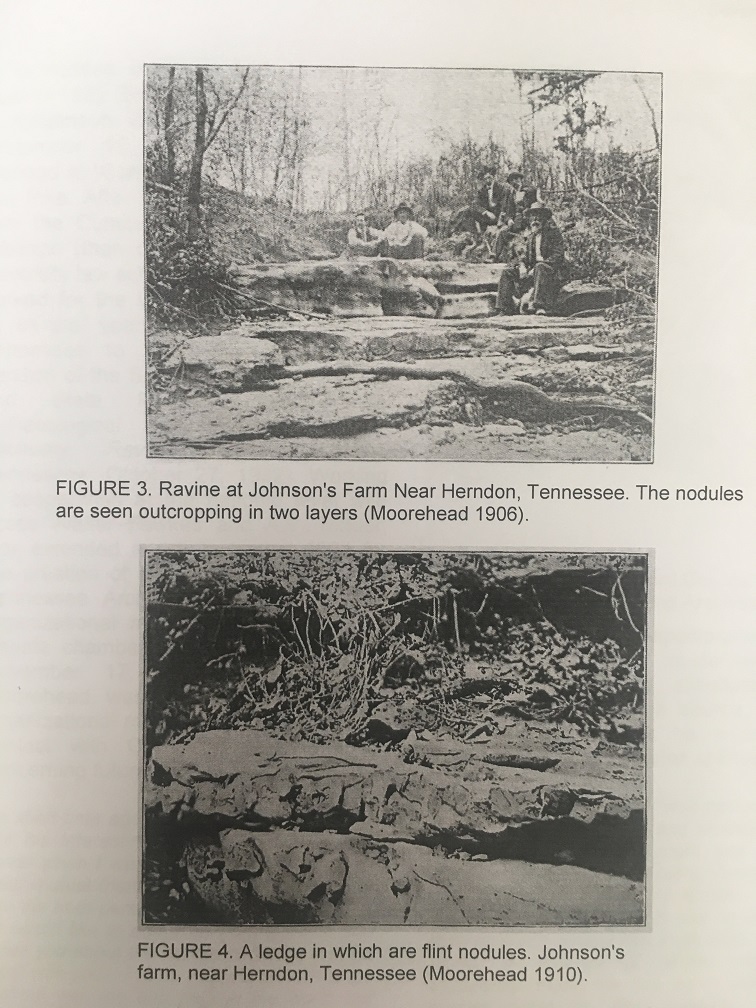

|

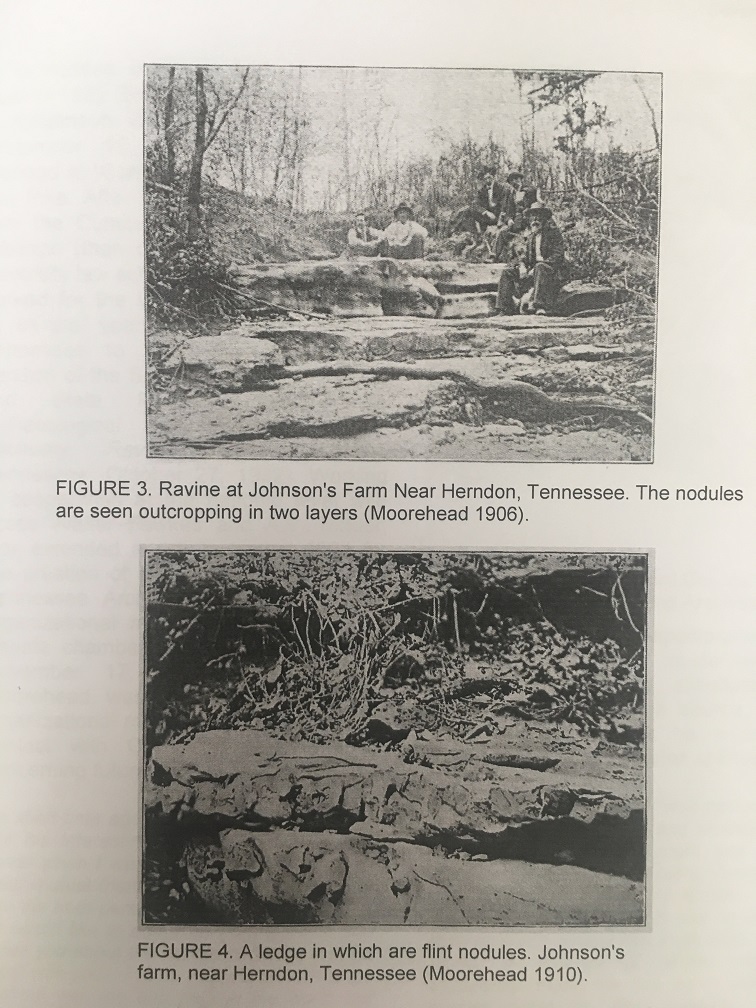

This photo is from Moorehead’s 1904

archeological journal highlighting a site that Carl immediately recognized on Little River

(Photo 28).As seen in this photo the site has chert nodules that would have been traded to

make projectile points or tools.

|

|

Viewed as a raw product, this is one of several

thousand pieces found as part of a large flint cache buried underground in Indiana on the Ohio

River. This blade would have been traded as a raw product with other Native American

entrepreneurs along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. There is no doubt in my mind that such

peoples had IQ’s similar to our own, traded with neighboring tribes, and their time was not

dominated by growing maize, huntng deer, or making pottery. Members of each settlement

obviously risked paddling great distanes for products not found locally: copper breastplates,

seashell gorgets, or granite. One knowledgable collector even believes that some Native

Americans along the Ohio River were our region’s first drug dealers. The theory is a minimal

charge was charged during the first bartered transaction for tobacco and a harder bargan was

driven once their naive trading partners had become addicted.

|

| |

Left: Unbroken mass

Right: Exposed chert ready for chipping out |

With the above as background information let us now attempt to clarify who were the

Mississippians who lived in Christian County and why did they make the effigy now housed in

the Metropolitan Museum of Art?

My initial inquiry began with a week-long Road Scholar’s program to the Cahokia Mounds

located across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri. For those of you not familiar with

Cahokia the settlement includes the largest Indian Mound in North America and the overall

settlement contains 120 mounds spread over 2,200 acres. The largest mound is 100 feet high,

105 feet long, and 48 feet wide. (Imagine a mound taller than the former First

City Bank building). As important, archeologists estimate that its construction required someone

to carry 22,000,000 cubic feet of dirt in woven baskets to build and maintain the mound.Two of

my iniital questions were ‘Why were the mounds built?” and “What motivation did the leaders

use to build the mounds?’”Although I respect everyone in this room, I cannot think of any logic

or mocho you could use to make me walk up and down Monk Mound carrying baskets filled

with dirt in the hot sun. Particularly if I or my family did not get to live at the top of the mound.

Regretably, after talking with several knowledgeable archeologists, no one can definitley

confirm why the mounds were built.Apparently, most mounds were built as a burial mound,

place of worship, or where the tribal chief or religious leader lived.The Cahokia mounds show

that multiple burials, perhaps of different leaders or family members, were buried over time on

top of each other. Cahokia mounds have yielded shells, pottery, weapons, and other items

needed in the afterlife.As part of our week’s activities we participated in archeological digs with

college students which although tempting (Photos 40-41) made me realize I would not have

been a good archeological student.As evidenced here, trained archeologists methodically dig 4

x 4 sites on their knees with a trawl in the sun all day long. An exciting day occured if one found

a shard of pottery or bone, which then had to be indexed using digital software.

|

|

|

Excavating a grid | Circle of wooden posts |

At Cahokia and elsewhere, many mounds include a contiguous circle of wooden posts, usually

identified as a Woodhenge. Again demonstrating exceptional intelligence and

knowledge, the wooden posts were positioned to accurately predict the spring and winter

equinoxes and other astronomical events. Perhaps with this type of astronomical knowledge the

leaders were able to justify their ability to live on top of the mound. An overview of all known

Indian mounds indicates that 89% are oriented to the east (sun worship?) and 71% are aligned to

the soltices. Some are clearly aligned to the Orion star belt and have a triangular arrangement.

(Even Hopkinsville’s own Edgar Cayce references the Mississippians and Indian mounds in

several of his 14,000 readings. Cayce states that the Mississippians travelled north from the

Yucatan Peninsula in Northern Mexico).

|

In addition, most Indian mounds were located within a

central plaza and surrounded by a wooden stockade (Photo). Whether as a result of diet,

sanitation, drought, pestilance, resource depletion, territorial conflicts, or a loss of faith in the

political or religious hierarchy, most Indian mounds were abandoned before 1500 AD. I found it

surprising that professional archeologists agree that the decline of the Mississipians was not

casued by disease or confrontation with European explorers. |

|

One of the highlights in researching this paper was to attend two Native American Artifact

shows, one in Owensboro and the other in Nashville. As a result I met several

fascinating people whose primary interests are the collection, sale, and purchase of Native

American antiquities. Once I gained their confidence I viewed private collections that equal or

exceed most museums. Although some vendor/collectors find & sell their own artifacts, most

now purchase all or part of private collections when such collections become available. Many

collectors from the 1930-1980’s who collected for fun are now forced to sell their collection for

health or living expenses. Many children or heirs of older collectors do not appreciate or want

their parent’s collections. Many farmers, now realizing the increasing value of Native American

artifacts, deny access to their property. Collectors usually pay cash or barter for items missing

from their private collections. Trade-show collectors enjoy the comradrie of fellow collectors

while bartering over specific projectile points, bannerstones, pipes, axes, or effigies. Rumor

has that it is not unusual for wealthy collectors to design their home with security systems and

cases that rival large museums. Regretably, one long-time local collector’s house burned down

and he lost his entire uninsured collection, representing many years of hard work. As fraudulent

items are becoming more common, particulalry when purchasing over the Internet, both amateur

and long-term collectors must be careful when purchasing items. Although most items are in the

$100-$5,000 range, this case of turkey tails sold for over $35,000. Well preserved and distinctive

effigies now sell in the $1,000,000-$2,000,000 range. For this reason

both shows had on-site experts with high grade microscopes with which, for a fee, a buyer could

better ensure the legitimacy of artifacts. In my opinion, the trend will continue for vendors to

purchase and sell the collections of older collectors, keep the best artifacts for their own, and

sell the highest priced items to wealthy collectors.

From a different perspective, which party has the strongest argument to collect, sell, or dispose

of Native American antiquities? On the one hand collectors are individuals who enjoy the rush

of finding and organizing their private collections. Rather than play golf or fish they spend many

weekends traversing creek beds, fields, and even caves to hopefully find one keepable projectile

point. So long as the property owner has granted permission, why should amateur collectors not

keep or re-sell their finds? Particularly when a collector is a true student of NativeAmerican

history, perhaps even more so than a trained archeologist?The harsh reality is that if such

amateur collectors do not search for such artifacts most will never be found and will remain

buried in the ground.

The best example of such a collector is Art Gerber of Tell City, Indiana. One of the highlights in

researching this paper was to meet Art at the Owensboro show. Art grew up searching for

artifacts along the Ohio River (and Christian County) and found the chert viewed earlier at “the

Crib Mound” in Spencer County, Indiana. As a well known collector Art was notified in 1986

through the “collector grapevine” that GE was demolishing a large Indian Mound in Posey

County, Indiana during a plant expansion.Although GE initially ignored the numerous diggers

who arrived each night to search for artifacts, Native American activists encouraged the U. S.

Attorney’s office to indict Art and others for violation of theArcheological Resource Protection

Act (ARPA) passed in 1979. As Art had taken several artifacts across state lines to

the Owensboro show, the government spent over $1,000,000 aggressively pursuing a

misdemeanor conviction. Once convicted, Art risked physical harm while spending one year in

three different federal prisons. Despite the financial asssitance of collectors across the nation.

Art was forced to sell some of his most prized artifacts to pay his legal and appeal bills. In Art’s

case, the government successfully argued thatARPA applied even though the artifacts were

found on private and not public land. One of the terms of his conviction was to return many

valuable artifacts to the government for re-burial at the GE site. To his dying day Art was

convinced that such artifacts were never reburied and were kept by others. Art was a

professional photographer and published an amazing book that contains some of the most

extraordinary artifacts that I have ever seen outside a museum. Art’s collection, found and

organized over a fifty year period, is a tribute to the craftsmanship of the Native Americans who

made the artifacts and to the dedication of collectors like Art who try to preserve and honor that

legacy.

Conversely, most Native Americans believe in a Great Spirit and the afterlife and believe

artifacts should remain or be reintered at the deceased’s initial burial site and not preserved in a

museum or collector’s basement. As the Great Spirit is perceived as omnipresent, many

locations (mountains, rivers, valleys . . .) are considered sacred. Consequently, most Native

Americans view any type of disturbance or excavation of a NativeAmerican grave as

sacrilegious. Since the passage of ARPA there has been a significant reduction in the

desecration of Indian burial mounds. Despite such sanctions, property owners confirm that it is

still common for some collectors to trespass and even leave trash and drink cans behind.

One might ask why Christian County produces so many artifacts? In my mind the primary

reason is the high grade St. Genevieve chert found along Little River. Christian County chert has

been found atWycliffe, Cahokia, and Poverty Point. Using the land where the North and South

branches of Little River meet near the Lafayette Road/Gary Lane bridge as an example, I easily

imagine 2-3 Indian mounds in the nearby fields. The navigable waterways provided access to

trade, chert, and defensive protection if attacked. My Grandfather used to say he found many

artifacts while coon hunting (particularly after a heavy rain) near the sewer plant.

In closing, the next time you sit on your deck or walk along Little River I encourage you to

imagine Paleo Indians stabbing a mastodon 10,000 years ago with a Clovis pont. Or imagine

1,000 years ago a NativeAmerican using an atlatl to kill a deer running across your yard.As in a

James Lee Burke or Tony Hillerman novel, imagine the many NativeAmericans who have

walked across your yard enjoying “your” sunrise or sunset. Now, no matter where you live in

Christian County, walk around your yard this weekend and with a bourbon in your hand ask

yourself this question: “Are similar Mississippian effigies, like the one housed in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art, buried in my backyard?”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

P.S.: The author contacted Dr. Michael Coe, a Mayan authority, regarding the figurine shown above. He responded:

Dear Wynn,

That’s a 100 per cent Mississippian piece, with no Maya influence. It’s very similar to a complete, half-kneeling figure nicknamed “Sandy” in the McClung Museum, Knoxville, TN. (see below)

I’m very familiar with “Sandy”, as he was in a museum case facing my desk in the UT Anthropology Department. My first teaching job was at UT, from 1958 to 1960, after which I left for Yale. I think that both the Met’s head and “Sandy" depict the same guy, probably an ancestral figure. There’s no Maya influence there — the Classic Maya civilization was in a deep nosedive before Mississippian got going. If there’s any influence from Mexico, it would be from the late Huaxtec civilization of the northern Gulf Coast.

During the summer of 1959, I was ordered to lead an archaeological survey of what is now the “Land Between the Waters” and the adjacent bottomlands of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. Much of it was going to be flooded by the rising waters behind the Barkley Dam, and I was supposed to dig all possible sites that would be destroyed, from Paleo-Indian through Mississippian — impossible!

I had two UT students as my helpers, and the crew was a bunch of white high school dropouts. I had a great foreman, though, Dumas Melton, a local whose Daddy had worked as a digger for Warren K.Moorehead, but Daddy was currently locked up in KY for moonshining. We based ourselves in Dover, TN, which was not all that far from your part of KY. Dover was reputed to have a three-way competition with Linton and Golden Pond — which town would have the most annual shootings.

But the area was loaded with ancient sites — some farmers had cigar boxes filled with Cumberland points, the local variant of Clovis. That summer we found a rich Archaic site on a bluff overlooking the Cumberland, and a large Mississippian village in a cornfield in the bottomlands. Incidentally, the star attraction in the Dover historical museum was an electric chair!

All the best,

Mike [Coe]

SANDY

Wikipedia

Wikipedia  Wikipedia

Wikipedia  Wikipedia

Wikipedia  The 'Mayan' figurine

The 'Mayan' figurine